Photo Credit | Stefan Bladh

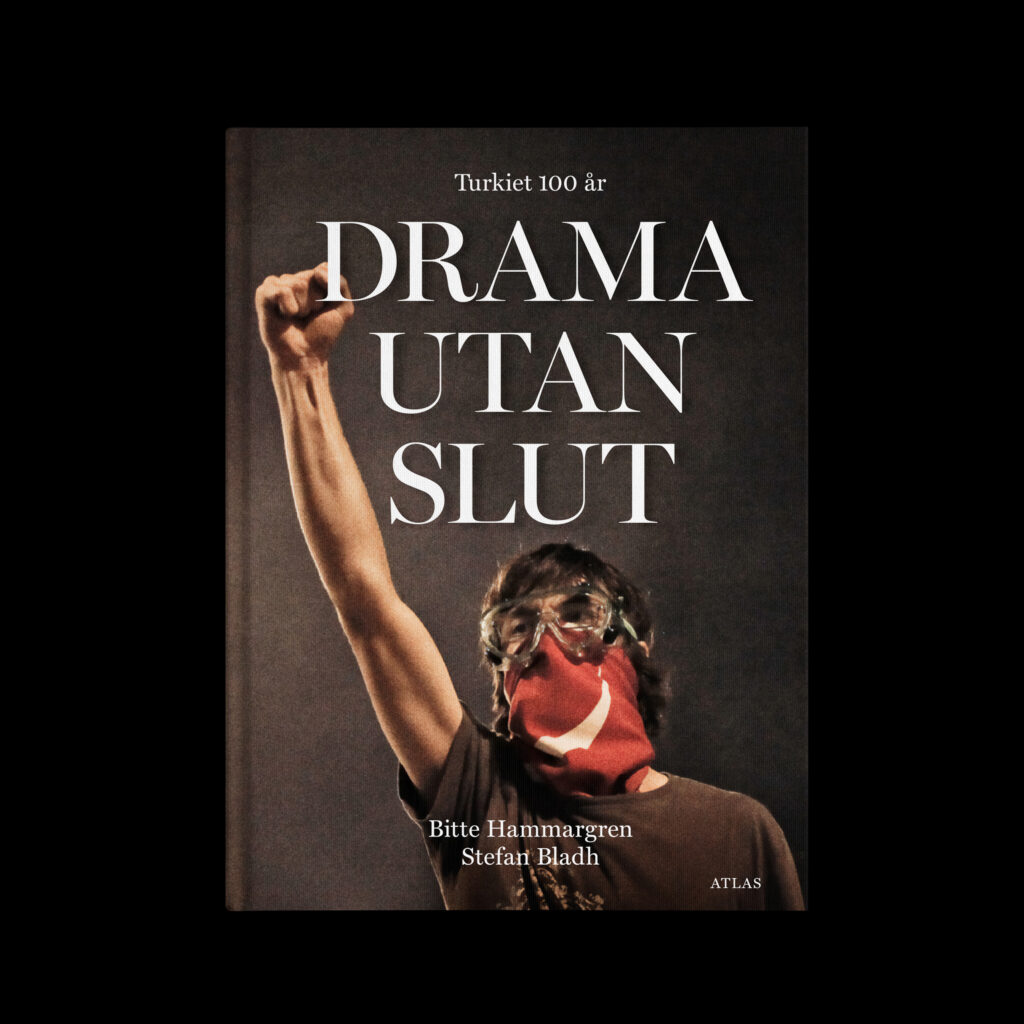

Bitte Hammargren’s new book, “Never-Ending Drama: Turkey at 100,” (Drama Utan Slut: Turkiet 100 år) offers an insightful retrospective on Turkey’s history, along with the photography of freelancer Stefan Bladh. As journalists, both Hammargren and Bladh have witnessed some of Turkey’s most pivotal moments in the last few decades. Hammargren sat down with FTP to discuss the book, her understanding of Turkish history, and her predictions for the future of the Republic.

What made you write this book and why?

Long before Sweden’s NATO accession was stalled by a Turkish veto, I thought that I may have something to tell a Swedish reader about the Republic. I have covered Turkey on and off as a journalist, and later as an analyst, for the last 30 years. Since I have often cooperated with the freelance photographer Stefan Bladh, who has 20 years of experience from Turkey, we decided to make this book together ahead of the Republic’s centenary. In the book, Stefan’s amazing photography is intertwined with my text.

Looking back, I realized that we have experienced some pivotal moments in Turkey, sometimes working in tandem, sometimes separately. In the early 90s, shortly after the sudden death of President Turgut Özal, I traveled to the southeast and got a sense of what the flare-up of the civil war between the state and the PKK meant.

During the first years of the millennium, I followed the AKP’s rise to power, including Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s first national electoral campaign in 2002, while he was banned from running for parliament. During the AKP’s first decade in power, Stefan and I saw many promising developments, such as economic growth, EU-oriented reforms, the Kurdish peace process, and a thriving civil society. But after the 2011 elections, when AKP scored almost 50 precent of the votes, we witnessed a transformation in many ways: increased crackdown on the media and free speech; the violent repression of the Gezi protest in 2013; the aftermath of the June 2015 elections, when the AKP temporarily lost its absolute majority in parliament, cancelled the Kurdish peace process and aligned itself with the ultra-nationalists of the MHP before the next elections the same year; the many U-turns in Turkey’s foreign policy; the miscalculations in its Syria policy and president Erdoğan’s increasing authoritarianism and the widespread purges that followed after the coup attempt in 2016.

As Turkey is heading for another pivotal moment, the May 14 elections, we felt that time was due to summarize what we have experienced. The result is our book, whose title can be translated as Never-Ending Drama: Turkey at 100, published by Bokförlaget Atlas in Stockholm.

When you look back at your own coverage and experiences in TR, what are the changes you’ve seen? Is it a country going in circles or progressing? Why and how?

The country changed tremendously and opened up during the first decade of the AKP’s rule, when the economic growth was astounding, the EU process was on the agenda and urbanization rampant. But, noticeably, the AKP’s increasing grip on power also led to a new wave of corruption and economic mismanagement, and with corruption comes a need for those in power to cover up.

In some respects, one could argue that history appears to be going in circles. Today’s inflation and loss of the lira give flashbacks to the economic crisis of the 90s. The 1999 Izmit earthquake, whose excessive deaths were blamed on the ruling parties at that time, paving the way for AKP’s rise to power, echoes the way that many Turks suffered from this year’s February 6 tremor. And just like in 1999, many of today’s survivors underline that earthquakes don’t kill, but bad buildings and a mismanaged state apparatus do.

Also, Erdoğan’s alliance with the MHP and his embrace of Turkish nationalism give flashbacks to the dark years of the 90s, when Özal’s peace process with the Kurds broke down. Ankara currently treats the Kurdish issue as terror problem only, without recognizing the state’s repression, thus refusing to acknowledge that it partly stems from Erdoğan’s failed Syria policy after the outbreak of the Arab spring. We all know how porous Turkish borders led to the weaponization of the Syrian uprising, the flow of weapons and foreign fighters and the rise of ISIS – only to be fought down by U.S.-supported Kurdish YPG forces who paved the way for Kurdish-led autonomy in northeast Syria, something Ankara refuses to come to terms with. So, in this regard, I would like to quote Mark Twain by saying that history is not repeating itself, but it often rhymes.

Your portrait of the enigma Erdoğan is striking in the book. How do you place him in Turkey’s 100th anniversary? He served longer than Ataturk. What will be his legacy?

One of Erdoğan’s goals ahead of the centenary is to overshadow Atatürk. President Erdoğan, needless to say, wants to build his legacy as the strongman and guardian of Turkey’s national interests. He certainly is a strongman, but he is also merciless in the way he silences anyone who dares to challenge him via his remote control of the judiciary. His foreign policy, characterized by his many U-turns and his impulsiveness, can by no means overshadow Atatürk’s, who as a president was not expansionist and focused on consolidating the new borders after the Lausanne treaty – while suppressing Kurds and Alevites at home, in a way which resembles today’s nationalism.

What conclusions and lessons do you draw in writing this remarkably deep book?

One of them is that a diehard Turkish nationalism cannot be the recipe for a thriving democracy in a multi-ethnic society. Looking back at history, another conclusion is that today’s Turkey needs to be understood through the lens of history and the breakup of the Ottoman Empire. One can trace a winding red thread from Atatürk to Erdoğan: authoritarianism and Turkish nationalism. But just as times have changed, they differ as leaders in many respects, such as their views on Europe, the borders, and Islam.

What do you expect to happen in the elections? Light at the end of the tunnel? Easier or harder times ahead? Why?

For President Erdoğan these elections will be like a make or break. If he fails to win, he might end up in court, facing corruption charges. For any political leader, losing an election is traumatic, but for an autocrat even more so. One way to measure the maturity of a democracy is whether a defeated leader is willing to acknowledge his loss or not.

It is by any means imperative that the results of the elections will be considered legitimate. Observers, both foreign and domestic, will thus have crucial roles to play. There are many ways to manipulate elections, and probably more so in the provinces that were hit by the February 6 earthquake. The risk of election fraud reminds me of the 2014 local elections, when there were power outages at the time of vote counting in many locations throughout Turkey. I happened to be in one of them, in Karaköy in Istanbul, at that time.

However, if the Table of Six and CHP’s Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu win both the parliamentary and presidential elections, Turkey stands a chance to dismantle the authoritarian presidential system and restore the integrity of the courts and other institutions. It gives more hope that the rulings of the European Court of Human Rights will be respected, and thus that Osman Kavala and Selahattin Demirtaş will be released. But there are many question marks left, even if the opposition wins. We don’t know if Turkey will reenter the Istanbul Convention on the rights of women and girls. And will a victory for the opposition lead to a guarantee for freedom of speech, the rule of law, and openings towards Cyprus and Greece, and Kurds domestically? That we don’t know, given how nationalistic instincts are ingrained in several parties. And it is hard to see a new Turkish government coming to peace with the Kurds in northeast Syria, and finding a future for the Syrian refugees in Turkey that does not lead to deportations at the end of the day.

It is the Turkish Republic’s 100th anniversary, how can we explain why TR has tumbled into this massive crisis at every level?

From my understanding, part of the Republic’s malaise can be explained by the opaqueness of the system; the refusal to recognize man-made atrocities of the past, for instance the denial of what happened to the Armenians and Syriac Christians even before the Republic was founded; the unhealed wounds among so many of today’s citizens and the unresolved Kurdish issue.

Photo Credit | Stefan Bladh

In the last paragraphs of our book, I quote İshak Alaton, a prominent businessman and philanthropist of Jewish descent, whom I got to know during my first visit to Turkey in 1992. When I saw him the last time, shortly before his passing in 2016, he appeared more pessimistic than before. He talked about how the Turkish Republic had been fed by fear and about the necessity of uncovering the brutalities of the past to reconcile and progress. I believe he was right in this regard.

For a stable and peaceful Turkey, how do you think these problems can be solved, given the culture and demographic changes and the global commotion? Any observations?

How about trying more transparency, for the present and the past? And let historians deal with the past, expose more of what is hidden in the archives, so that today’s citizens can discuss, learn, and acknowledge what has happened to their ancestors? Let people from various backgrounds honor their loved ones who went missing in unknown locations and hidden graves. Acknowledge the multi-ethnic history of Anatolia, so that places which used to be inhabited by Greeks, Armenians or Syriacs can have their old names restored in tandem with the current Turkish names of locations. Let the Kurdish language thrive, in parallel to the Turkish language, and acknowledge that the nature of the Republic is multi-ethnic. I believe that Turks who said that “We are all Hrant Dink”, after the assassination of the Turkish-Armenian intellectual in 2007, know what it takes to pave the way for a stable and peaceful Turkey.