Turkey held its first presidential runoff elections on May 14 and 28. Polls prior to the election showed Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s “People’s Alliance” and Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu’s “Nation Alliance” in a close competition, with both candidates in the 40 percent range, which suggested the People’s Democratic Party (HDP) and Kurdish voters would be the key to electoral victory.

The Kurdish movement has entered into elections since 1991 under ten different parties as a result of continuous threats of party closures, and the tenth of these, the HDP, was under threat of closure due to an ongoing court case and decided to enter the elections with a “backup” party – the Green Left Party (YSP).

The leadership of the Green Left Party established the Labor and Freedom Alliance prior to the election with the Turkish Workers Party (TİP) and other left wing parties.

The Green Left Party’s leadership, having decided not to nominate a presidential candidate from their own alliance, gave their support to Kılıçdaroğlu and with this support Kılıçdaroğlu led Erdoğan in pre-election polls.

However, while this support buoyed Kılıçdaroğlu, it became Erdoğan’s biggest trump card at the same time. Despite the harm caused by high inflation and the earthquakes, Erdoğan spent the whole campaign charging Kılıçdaroğlu with having garnered the support of the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK). He even released a deep fake video purporting to show Kılıçdaroğlu meeting with PKK leader Murat Karayılan. The video ultimately boosted support for Erdoğan’s campaign in the country’s nationalist and conservative regions.

Given the fact of the HDP’s strength in Kurdish regions, those regions were among those that voted most heavily for Kılıçdaroğlu.

Source: The 20 provinces where Kılıçdaroğlu won the highest percentage of votes in the second round.

Out of the 20 regions that voted most strongly for Kılıçdaroğlu, 12 of them were Kurdish. At the district level, 15 of the strongest districts for Kılıçdaroğlu were predominantly Kurdish.

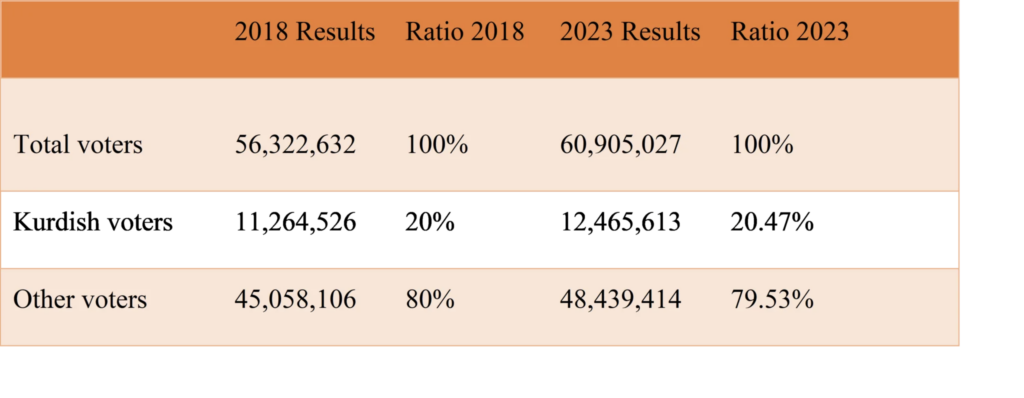

However, there were striking results outside of the fact that Kurdish voters supported Kılıçdaroğlu in these two rounds of voting. According to data collected by Rawest Research and the Kurdish Studies Center, Kurds could have made up almost 20 percent of the electorate in Turkey.

Source: Projection based on research previously collected by Rawest and the Kurdish Studies Center.

Relative to the 2018 Presidential Election, 2023 participation rates fell in the regions in which the HDP performed the strongest. However, this result was not a surprise to us at Rawest Research. Seeing this drop from our research prior to the election, we analyzed the causes. The elections bore out our hypotheses.

Let’s look at why votes fell for HDP or the YSP because in truth there is no single reason.

First, the most interesting reason is lethargy caused by the lowering of the parliamentary threshold. Prior to these elections, political parties needed to secure 10 percent of the vote to enter parliament, but ahead of these elections that threshold was lowered to 7 percent. It appears that slackened support can be credited to the fact that less mobilization was needed to pass the threshold.

Second, not only was HDP under legal pressure, many of its previous parliamentarians and directors are in prison. The most important of these is undoubtedly Selahattin Demirtaş, who has been in prison for the past seven years. Demirtaş was a founder of the HDP, and among all the Kurdish parties established since 1991, he has become the most popular politician and leader.

Although he is able to actively speak and tweet with the assistance of his lawyers, Kurdish voters’ interest in Turkish politics has waned without a fully engaged leadership. With the pressure and arrests, party organizations, especially in the more provincial areas, have lessened their political activity, and the main cadres of the movement have remained out of politics. The unilateral replacement of HDP mayors in the Kurdish provinces with AKP custodians also contributed to the lack of visibility and reduced strength of the party.

Third, another interesting reason for the depressed turnout is that after long years of ignoring Kurdish voters, and significant historical baggage, the Republican People’s Party (CHP) suddenly turned into a party willing to court Kurdish votes. While the AKP and the HDP/YSP lost votes in Kurdish regions, the CHP votes tripled or quadrupled. The CHP elected a parliamentarian from Diyarbakır for the first time in half a century. They will send deputies to the Parliament from Şanlıurfa and Ağrı. They nearly reached the threshold to send deputies in Van and Mardin.

The fourth reason for the decline in HDP voting is that the traumatic experience in Kurdish cities following the collapse of the AKP’s peace process with Kurdish groups in 2015-2016 is still ongoing. Despite the AKP’s nationalist rhetoric and alliance with an ultranationalist party, the Nationalist Action Party (MHP), they lost fewer votes than expected in this election. Here also, the alliance the AKP formed with the Kurdish Islamist party HÜDAPAR allowed the AKP to send an effective and positive message to pious Kurds.

Fifth, one of the ironic reasons for the HDP/YSP’s decline is that they appear to have chosen the wrong alliance. They had a prominent place in the Labor and Freedom Alliance, but in many regions of Turkey’s west, voters with socialist or social democratic leanings that would have gone to HDP instead went to the Turkish Workers Party (TİP), who are now sending four MP’s to the parliament.

Sixth, following Demirtaş’s 2014 presidential campaign and the nomination of an Alevi with Kurdish roots in Kılıçdaroğlu, the CHP had reoriented itself to begin to appeal to regions and municipalities with Kurdish Alevi populations.

Seventh, and finally, one of the factors was the centralized decision making of the Green Left Party’s candidate list, which resulted in some candidates not being familiar to some of the cities and reduced excitement. After the election, former HDP co-chairman Demirtaş also criticized this centralized practice in his election analysis which he sent from prison.

Another stunning result of this election was that the participation rates in Kurdish regions fell below average for Turkey as a whole.

Relative to 2018, the electoral participation rates in the HDP’s strongest regions all fell. The participation rate in the first round of the election on May 14 was below the average of all Turkey’s regions. However, in the second round on May 28, participation rates in these regions fell yet again.

Source: Provincial turnout rates for the May 28 Presidential Elections.

The drop in HDP voting rates after the first round of the elections can be explained by a number of factors.

One reason for the drop in participation rate was Kılıçdaroğlu’s turn before the second round to a more nationalist tone and his attempt to secure the 5 percent of votes won by Sinan Oğan in the first round by signing a protocol with ultranationalist party leader Ümit Özdağ. One of the protocols promised that there would be restricted legal action to undo the appointment of AKP mayors to HDP municipalities. It’s possible that this nationalist tone and these protocols decreased Kurdish motivation to vote for Kılıçdaroğlu.

And yet, in the second round, the regions with the highest support for Kılıçdaroğlu were still the Kurdish regions. However, from the point of view of opposition supporters in Western Turkey, this drop in participation rate was the reason for their disappointment. Kurdish voters are still included on the list of reasons for the electoral defeat.

In fact, Kurds did not vote for rising nationalism and against Erdoğan just so democracy could come back to Turkey. The Kurdish vote is also an ethnic vote. The first criteria in voting is a security issue. Rather, a determination of which candidate or party will cause the least harm. It was both unrealistic and disappointing to ignore the security concerns of Kurds while still expecting them to be the saviors of democracy.

Whether the HDP will be shut down or not, what Kurdish MPs will do to oppose strengthened nationalism in the parliament, whether or not Kurds will cooperate with the CHP and the Nation Alliance in next year’s local elections, and how Kurdish politics will change in reaction to the four MPs representing HÜDAPAR are all open questions.

There is uncertainty in all of this.

What is not uncertain is that Kurdish voters played a key role in the 2019 local elections in Istanbul, Ankara, Adana, Mersin, and other cities where the opposition candidates were victorious.

But how these voters will be given a prominent role without conceding nationalism to Erdoğan’s regime will determine the fate of future elections.

This article was originally published by FPRI.

The views and opinions expressed above are those the author’s and do not reflect those of the Free Turkish Press.