‘Turkey’s geography and membership in NATO have long given the country an influential voice in foreign policy, but the assertive policies of President Erdogan have complicated its role.’

Erdogan and his AKP, a conservative party with Islamist roots, came to power in 2002, following a decade marked by political instability and a financial crisis. The AKP advanced economic and political reforms to bring Turkey closer in line with EU standards, and the country’s economy grew by 7.5 percent on average annually between 2001 and 2011. On foreign policy, the AKP’s motto was “zero problems with neighbors,” and Ankara aimed to expand Turkey’s influence by building trade ties, encouraging democracy, and emphasizing its Islamic identity.

But by the late 2000s, the AKP had become more authoritarian. It consolidated control over media organizations, purged the military of perceived dissidents, prosecuted and jailed critics, and quashed protests.

In 2016, Erdogan seized on an attempted military coup to crack down further on his perceived opponents, who he alleges are led by Fethullah Gulen, a cleric living in exile in the United States who was once Erdogan’s ally.

Through a referendum the following year, Erdogan replaced the country’s parliamentary system with a presidential one; abolished the office of prime minister, among other major changes; and effectively rendered himself Turkey’s sole power holder.

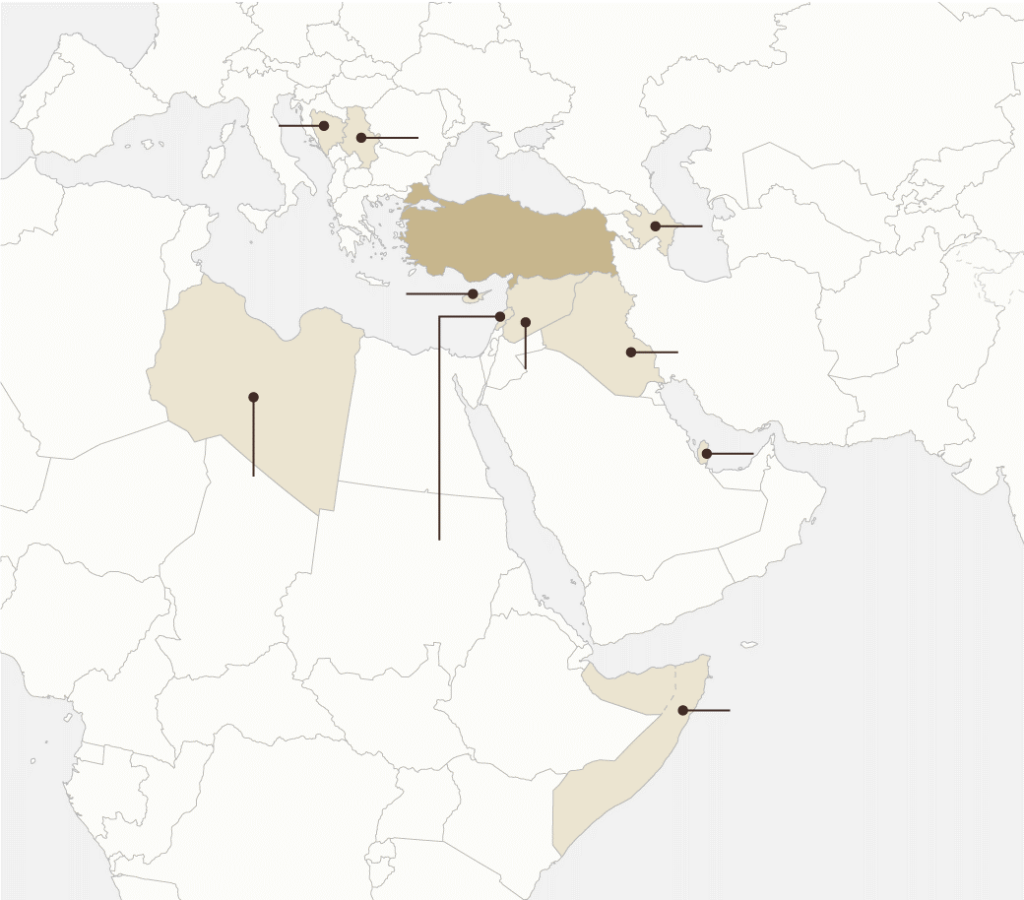

Erdogan has engineered an assertive shift in foreign policy that focuses on expanding Turkey’s military and diplomatic footprint. To this end, Turkey has launched military interventions in countries including Azerbaijan, Iraq, Libya, and Syria; supplied partners such as Ethiopia and Ukraine with drones; and built Islamic schools abroad.

Turkey’s Military Presence Abroad:

The Kurds, a primarily Muslim ethnic group spread across not only Turkey but also Iran, Iraq, and Syria, are Ankara’s “dominating security concern,” says CFR’s Henri J. Barkey. Making up one-fifth of Turkey’s population, the Kurds have long raised fears in Ankara over their demands for more autonomy or, in some cases, independence.

Turkey has waged war against the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), a militant group that aims to establish a Kurdish state, since the 1980s—a conflict that has killed tens of thousands of people.

Erdogan’s government initially supported greater social and political rights for Kurds, but it abandoned that stance after facing backlash, particularly from ultranationalists within the AKP’s coalition. Peace talks with the PKK that began in 2012 have collapsed, and the government sought to shut down the leading Kurdish opposition party ahead of elections in May 2023. In light of the continued tensions, some observers worry more Kurds will abandon political solutions and turn to violence instead.

Fears of Kurdish nationalism have also shaped Erdogan’s interventionism in the Syrian civil war. Since 2016, Turkey’s military has occupied parts of northern Syria to push Kurdish forces away from the countries’ shared border, prevent them from consolidating their territory, and pursue the PKK.

Turkey originally sought to overthrow the Syrian regime, but by late 2022, the two sides were in talks to restore ties. A series of earthquakes that devastated both countries in February 2023 may have accelerated normalization efforts, according to some experts, but the talks have yet to result in a deal.

Ankara aims to consolidate opposition to Kurdish forces and send Syrian refugees back home. The AKP’s political coalition capitalized on mounting anti-refugee sentiment among the Turkish public to gain support ahead of the 2023 elections, which saw it win a majority of seats in parliament.

Other regional flash points: The AKP’s “zero problems with neighbors” policy has been undermined by tensions in several areas. But with Turkey’s economy faltering, Ankara is now seeking to repair ties with governments it once quarreled with in the hopes of helping its standing in Washington and securing much-needed foreign investment, CFR’s Steven A. Cook writes.

Quartet. Turkey’s ties with Bahrain, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), an informal grouping known as the Quartet, frayed after Ankara supported the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt during the 2011 Arab uprisings. Relations worsened further after Saudi agents assassinated journalist Jamal Khashoggi in Istanbul in 2018 and Ankara deepened trade and energy ties with Tehran, Riyadh’s rival.

However, as Turkey’s economy struggles from reduced trade and investment, Erdogan is attempting to improve relations with these countries.

Israel. Turkey was the first Muslim-majority nation to recognize the Jewish state, and the two countries cooperated closely on intelligence matters in the late 1990s and early 2000s. The relationship soured as Erdogan championed Palestinian nationalism, including by hosting Hamas members, and publicly advanced antisemitic views. The countries downgraded ties in 2018 but restored them in 2022 as part of the regional rapprochement.

Armenia. During World War I, the Ottoman Empire killed more than 1.5 million Armenians, a mostly Christian minority many viewed as a threat to the state, and expelled many more. Turkey emphatically denies that this policy constituted genocide, and it has long lobbied the United States and others against using the designation. These tensions persist: Turkey has supported its ally Azerbaijan in its conflict with Armenia over the contested Nagorno-Karabakh region, a stance that continues to hinder normalization with Armenia.

Mediterranean. Relations with Greece and Cyprus are long-standing issues, and these countries have not featured in Turkey’s recent drive to mend ties. Greece fought the Ottoman Empire for its independence, and Athens and Ankara have come close to war on a handful of occasions in recent decades. In 1974, Turkey invaded and occupied half of Cyprus, which is divided between Greek and Turkish populations, fearing Greece was poised to annex the island; a UN peacekeeping force is still stationed there.

Turkey’s expanding territorial claims in Eastern Mediterranean waters, where it seeks to exploit oil and gas to reduce its dependence on imported energy, have angered the EU and fellow NATO members, such as France. Ankara’s pursuit of energy resources also led it to intervene in the Libyan civil war, after Libya’s internationally recognized government supported its claims.

——

Turkey formalized its Cold War–era alignment with the West by joining European institutions, such as the Council of Europe, a human rights organization, and the European Economic Community (EEC), the precursor to the EU. EEC membership led to the creation of a Turkey-Europe customs union, which allowed for the free movement of goods. Millions of Turks also migrated to Europe, particularly Germany, as guest workers.

The hope of joining the EU, Turkey’s biggest trade and investment partner, has been a major driver of policy and spurred the AKP’s early reforms. Formal negotiations began in 2005, but talks have stalled for a range of reasons, including opposition from many EU members, Turkey’s democratic backsliding, and its growing repression of the press, dissidents, ethnic minorities, and LGBTQ+ people.

Refugee crises have further strained Turkey-EU relations, as Ankara has wielded its refugee population—the largest in the world as of October 2022—as leverage over Brussels.

In 2016, after the number of asylum seekers entering Europe via Turkey surged, Ankara agreed to block migrants from journeying to EU countries in return for increased aid. However, Turkey has threatened to “open the gates” in response to European criticism on several occasions.

——

During the Cold War, maintaining a united front against the Soviet Union overshadowed tensions between the NATO allies, which included Turkey’s invasion of Cyprus and denial of the Armenian genocide. Without a common enemy, however, they’ve drifted apart. CFR’s Cook says that Washington now shares few interests with Ankara, and argues for reducing U.S. reliance on Turkey, including by seeking alternative military bases elsewhere.

Cook and others point to Ankara’s closeness to U.S. adversaries, including Iran: Washington says a Turkish state-owned bank, Halkbank, tried to circumvent U.S. sanctions on Tehran from 2012 to 2016.

The Syrian war further tested relations. U.S. forces in Syria collaborated with Kurdish groups linked to the PKK, angering Erdogan. Perhaps chief among Turkey’s complaints is its accusation that the United States and NATO helped foster the 2016 coup attempt. Ankara cites Washington’s refusal to extradite Gulen, the alleged mastermind, as evidence; most independent experts are skeptical.

In 2019, Turkey defied U.S. warnings not to purchase Russia’s S-400 missile defense system, which is incompatible with NATO systems. Ankara argued that it needed to upgrade its air defenses but was refused access to the U.S.-made Patriot system.

The move prompted sanctions against Turkey as well as the country’s removal from the United States’ F-35 fighter jet program. Washington insisted that Russian technicians maintaining the S-400 could gain access to the jets’ stealth capabilities. Experts such as CFR’s Cook and Max Boot say the affair demonstrated Turkey’s unreliability as a U.S. and NATO partner.

Despite these strains, Erdogan enjoyed an amicable relationship with President Donald Trump, who de-emphasized human rights and rule-of-law issues. In comparison, President Joe Biden kept Ankara at a distance early in his administration; he excluded Erdogan from his 2021 Summit for Democracy and referred to the Armenian genocide officially.

But Turkey’s support for Ukraine against Russia, and for expanding the NATO alliance, has shifted the calculus. In July 2023, the Biden administration said it will push forward with plans to sell F-16 jets and other hardware to Ankara—pending congressional approval—saying that this would serve U.S. interests and NATO unity.

The shift from Washington came after Ankara reversed its opposition to Sweden’s bid to join NATO, which had threatened to further strain Turkey’s ties to others in the alliance.

As tensions with the West persist, Turkey is exploring other relationships, particularly with China and Russia. It has bolstered ties with Beijing, which became Ankara’s largest import partner in 2021. In 2015, Turkey joined the Belt and Road Initiative, giving it access to non-Western financing for infrastructure projects, including nuclear- and coal-powered energy plants, and spurring foreign investment from China.

China has also provided Turkey with billions of dollars in loans and cash swaps since 2016. Meanwhile, Turkey mostly overlooks the repression of China’s Uyghurs, a Turkic Muslim minority with members in Turkey. In 2009, Erdogan described China’s abuses of Uyghurs as “genocide,” but since then, Ankara has not publicly pressed the issue.

Relations with Russia are likewise complex. In addition to the S-400 missile systems, Ankara and Moscow collaborate on infrastructure projects, such as the TurkStream natural gas pipeline and Turkey’s first nuclear power plant. Additionally, Turkey depends heavily on Russian energy imports. However, the two countries have backed opposing sides in recent conflicts, including the civil wars in Libya and Syria and the 2020 conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan.

As for the Russia-Ukraine war, Turkey has sought a balance between both countries. Turkey has supplied Ukraine with drones, supported a UN vote condemning Russia’s invasion, banned all combat ships from the Turkish Straits, and blocked Syria-bound Russian aircraft from Turkish airspace. On the other hand, it has opposed Western sanctions on Russia due to its own energy needs. Turkey aims to position itself as a mediator in the conflict, analysts say, and it helped broker a deal to allow Ukrainian food supplies to reach global markets.

Some experts say the success of Erdogan and the AKP in the 2023 elections likely means a continuation of the president’s policy trajectory over the next five years. He ultimately seeks to elevate Turkey’s international status, establishing it as the representative of the broader Muslim world and emphasizing a “bigger than five” agenda that would see international leadership expand beyond the UN Security Council’s five permanent members.

As part of this vision, Turkey has pushed its favored approach to Islamic law, especially in Africa, in competition with Saudi Arabia. Other experts expect some foreign policy changes in Erdogan’s new term.

Erdogan’s unchecked authority could be particularly dangerous for Turkey, Barkey argues. “Erdogan inhabits an echo chamber of sorts,” he writes. “In the near term, this will translate into policy making that is simultaneously fast moving yet prone to potentially serious errors in judgment as well as ordinary mistakes. Its long-term consequences are difficult to discern at this stage.”

______

This article was originally published by CFR. This is a shortened version.

The views and opinions expressed above are those of the author(s) and do not reflect those of the Free Turkish Press.